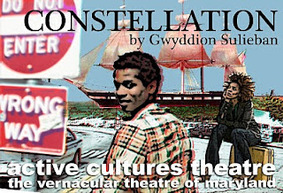

Playwright Interview Part Two - The Play and Beyond

Jacqueline Lawton: The Constellation is about a man who steals a ship, but not just any ship, a 150 year old sloop-of-war, the USS Constellation, which is docked in Baltimore’s Inner Harbor. What compelled you to write this play? How did you decide which characters/points of views would appear in the play?

Gwydion Suilebhan: I have been thinking and writing about the USS Constellation for just about as long as I can remember. The first poem I ever published, in fact, was a small piece about the ship called Her Departure. To me, the ship is the soul of the city. The city only exists (like most cities) because of its connection to the water, and that 150 year-old boat is a living symbol of that connection, or what remains of it. I’ve always thought of it as the heart of the city, embodying all the racial and military and nautical narratives that comprise the city’s story. I’ve also always been conscious, for most of my life, of the fact that the ship largely seems to be overshadowed by the glitz and glitter of the inner harbor’s “main attractions” – the aquarium, the science center, the shops and restaurants, even the merry-go-round, none of which contain any of the history. So part of what compelled me to write this play was an urge to say to the city “Hey! Look at what’s sitting right there! Right in front of you! Do you have any idea how important that is? It’s everything!”

I think the characters (and their points of view) come partially from the same sort of place. The Tour Guide’s voice is one that calls our attention to the violence and genocide in the ship’s history, which we should probably never forget. The Man’s voice represents the abolition and liberation that the ship stands for as well. The Woman speaks, I think, for our general alienation from all of that history, and the Boss for our urge to commodify and transform that history until it no longer resembles the truth.

Perhaps more importantly, though, the characters come from somewhere far more personal. When I first began drafting the play, I was going through a major life change. I was daring to do something that felt almost as impossible to me as stealing the USS Constellation would feel – something I was nonetheless absolutely compelled to do. So the characters are also manifestations of my own struggle to take the first step of that journey – the part of me that was old and weary and needed the change (Man), the part of me that was young and rebellious and had the energy to change (Tour Guide), the part of me that was afraid of the change (Woman), and the part of me that actively tried to stop myself from changing (Boss).

JL: One of the more serious issues in this play is homelessness. What led to the decision to make Man and Woman homeless? Did you always know that they would be homeless? What relationship to the city do you feel the homeless community has, that those with homes, do not have?

GS: Decisions like this, for me, are always made instinctively. I didn’t consciously say “I think I’ll make them homeless because…” I just started writing and that’s what came out of me. It probably had a lot to do with the changes I was going through and a feeling of being alienated from my own “emotional home.”

As the characters developed, however, it became clear to me that Man and Woman were both homeless in very different ways. Woman is homeless in a more conventional sense – she’s been battered and victimized and is trying very hard to make a new, safe home for herself. Man is homeless in a more intentional way – he’s off the grid, living unconventionally, not willing to participate in any of the behaviors that make us modern humans. He chooses to live as an outsider, on his own terms. This is what helps him see things as he believes they’re supposed to be, not as they are.

As for the relationship that the homeless community has with the city: I’m wary of generalizations and assumptions. From the outside, homeless people have always looked like ghosts to me – almost (but not quite entirely) invisible, capable of sending a kind of generalized anxiety through you when you actually stop to notice them, not really fully connecting and interacting with the world. It’s almost as if they symbolize our urban angst… except for the fact that they don’t symbolize anything at all, in reality. They’re people – disenfranchised, often disabled (in various ways) people, each with a unique story, and each probably relating to the city in a unique way.

JL: Talk to me about how you named the characters in The Constellation.

GS: I resisted giving them names because I wanted to heighten their existence as symbols. This play is a fable – a modern fable. Man, Woman, Boss, and Tour Guide are the contemporary equivalents of Aesop’s Crow, Fox, Ant, and Grasshopper or the Brothers’ Grimm’s Princes and Princesses and Tailors and such. In practice, though, I really think it doesn’t affect the audience’s experience of the play that they don’t have names. There’s never a moment at which you think “Now who’s that again?” They acquire their individuality by virtue of the fact that they’re all so different than each other.

JL: Which character in The Constellation shares your passion for Baltimore? Which character in The Constellation sees Baltimore in a way that opened your eyes to the city and revealed it to you in a new way?

GS: This is difficult to answer (like many of your very thoughtful questions). As I’ve said already, I think all of the characters are parts of me, and I think they’d all appreciate facets of Baltimore that I appreciate, too. The Tour Guide loves the history like I do, and he probably also shares my passion to talk about it. The Man shares my urge to idealize it, I think. The Woman might, if someone asked her, say a few nice words about the simpler things the city has to offer: pretty homes, nice churches, a beautiful hotel or two. And even the Boss, I feel certain, would brag about the extensive new commercial developments that have helped the city revitalize itself, at least in some areas.

Researching homelessness in Baltimore – for Man and Woman – taught me a few new facts about the city, but I honestly can’t say that I saw it in a new way. The new way I would like to see it is from the deck of the USS Constellation, the skyline receding into the distance as the ship heads out into the harbor… but I suspect that’s never going to happen. (I promised I’d bring it back!)

JL: Which aspect of Woman’s character do you most relate to? What aspect of Boss’s character do you most relate to?

GS: I think I’ve answered this already: Woman’s fear of change and her desire for stability and Boss’s need to control and prevent change from happening. It took me several drafts, though, to get to the point at which I could answer that question. I demonized them both so much early on, and I had to accept them as necessary parts of the story (and as parts of what I was going through). Whoever said that writing wasn’t therapeutic was foolish; writing that’s only therapeutic, however, is far too small.

JL: What was the most challenging part of writing The Constellation? Which character’s voice was the most difficult to capture?

GS: Finding the right – the most genuine – way for the ship to get out of the harbor was the most difficult challenge. In various drafts, various characters (including a few who are no longer in the play) were on board when it sailed out, but it wasn’t until I realized that the play was about the male characters finding each other and jointly leaving the female characters behind (while the female characters both resisted and facilitated that departure) that the ending finally made sense to me. The most difficult voice to capture was the Boss. I disliked her so much at first, and I had to ease my way into finding her humanity, to understanding that she wasn’t despicable in her own life’s story, and to give her a vision of her own to give voice to throughout the play.

JL: As this interview is taking place, you’re in the middle of rehearsals for The Constellation. What has surprised you about the play?

GS: The play just keeps getting funnier and funnier! (Especially as I chip away at and remove all the unessential bits of language that sometimes bog my early drafts down.) I’m actually always surprised by the humor in my work – people generally think of me as a comedic playwright, I’m led to understand, but I almost never sit down with the intent to write something funny. I’ve been catching myself laughing at my own lines, which I almost never do (and which is probably a testament to this talented cast). It’s great fun.

JL: What next for you as a writer?

GS: I’ve just finished a long run of productions in DC, New York, Chicago, and Los Angeles, and for the first time in a long while my calendar’s somewhat open… which is perfect timing, because I’m about to become a new father, and I know that’s going to claim an impossibly large amount of energy. (At this point, I’m going on complete trust and the promises of some dear playwright friends who’ve also made this transition and managed to keep working.) I have two plays in progress that will compete for whatever attention I do have. Midway is an existential comedy (in the vein of my earlier play Let X) that draws on my time working as a carny. Hot & Cold is a Grand Guignol-style play that juxtaposes the hot zone of a Level IV Biohazard Lab and the cold chill of an ordinary, middle class kitchen on Christmas morning – scientists in terror and a family farce, side-by-side, in an exploration of our national fear of infection. One of them will surely demand to be written first. We’ll see.

Gwydion Suilebhan: I have been thinking and writing about the USS Constellation for just about as long as I can remember. The first poem I ever published, in fact, was a small piece about the ship called Her Departure. To me, the ship is the soul of the city. The city only exists (like most cities) because of its connection to the water, and that 150 year-old boat is a living symbol of that connection, or what remains of it. I’ve always thought of it as the heart of the city, embodying all the racial and military and nautical narratives that comprise the city’s story. I’ve also always been conscious, for most of my life, of the fact that the ship largely seems to be overshadowed by the glitz and glitter of the inner harbor’s “main attractions” – the aquarium, the science center, the shops and restaurants, even the merry-go-round, none of which contain any of the history. So part of what compelled me to write this play was an urge to say to the city “Hey! Look at what’s sitting right there! Right in front of you! Do you have any idea how important that is? It’s everything!”

I think the characters (and their points of view) come partially from the same sort of place. The Tour Guide’s voice is one that calls our attention to the violence and genocide in the ship’s history, which we should probably never forget. The Man’s voice represents the abolition and liberation that the ship stands for as well. The Woman speaks, I think, for our general alienation from all of that history, and the Boss for our urge to commodify and transform that history until it no longer resembles the truth.

Perhaps more importantly, though, the characters come from somewhere far more personal. When I first began drafting the play, I was going through a major life change. I was daring to do something that felt almost as impossible to me as stealing the USS Constellation would feel – something I was nonetheless absolutely compelled to do. So the characters are also manifestations of my own struggle to take the first step of that journey – the part of me that was old and weary and needed the change (Man), the part of me that was young and rebellious and had the energy to change (Tour Guide), the part of me that was afraid of the change (Woman), and the part of me that actively tried to stop myself from changing (Boss).

JL: One of the more serious issues in this play is homelessness. What led to the decision to make Man and Woman homeless? Did you always know that they would be homeless? What relationship to the city do you feel the homeless community has, that those with homes, do not have?

GS: Decisions like this, for me, are always made instinctively. I didn’t consciously say “I think I’ll make them homeless because…” I just started writing and that’s what came out of me. It probably had a lot to do with the changes I was going through and a feeling of being alienated from my own “emotional home.”

As the characters developed, however, it became clear to me that Man and Woman were both homeless in very different ways. Woman is homeless in a more conventional sense – she’s been battered and victimized and is trying very hard to make a new, safe home for herself. Man is homeless in a more intentional way – he’s off the grid, living unconventionally, not willing to participate in any of the behaviors that make us modern humans. He chooses to live as an outsider, on his own terms. This is what helps him see things as he believes they’re supposed to be, not as they are.

As for the relationship that the homeless community has with the city: I’m wary of generalizations and assumptions. From the outside, homeless people have always looked like ghosts to me – almost (but not quite entirely) invisible, capable of sending a kind of generalized anxiety through you when you actually stop to notice them, not really fully connecting and interacting with the world. It’s almost as if they symbolize our urban angst… except for the fact that they don’t symbolize anything at all, in reality. They’re people – disenfranchised, often disabled (in various ways) people, each with a unique story, and each probably relating to the city in a unique way.

JL: Talk to me about how you named the characters in The Constellation.

GS: I resisted giving them names because I wanted to heighten their existence as symbols. This play is a fable – a modern fable. Man, Woman, Boss, and Tour Guide are the contemporary equivalents of Aesop’s Crow, Fox, Ant, and Grasshopper or the Brothers’ Grimm’s Princes and Princesses and Tailors and such. In practice, though, I really think it doesn’t affect the audience’s experience of the play that they don’t have names. There’s never a moment at which you think “Now who’s that again?” They acquire their individuality by virtue of the fact that they’re all so different than each other.

JL: Which character in The Constellation shares your passion for Baltimore? Which character in The Constellation sees Baltimore in a way that opened your eyes to the city and revealed it to you in a new way?

GS: This is difficult to answer (like many of your very thoughtful questions). As I’ve said already, I think all of the characters are parts of me, and I think they’d all appreciate facets of Baltimore that I appreciate, too. The Tour Guide loves the history like I do, and he probably also shares my passion to talk about it. The Man shares my urge to idealize it, I think. The Woman might, if someone asked her, say a few nice words about the simpler things the city has to offer: pretty homes, nice churches, a beautiful hotel or two. And even the Boss, I feel certain, would brag about the extensive new commercial developments that have helped the city revitalize itself, at least in some areas.

Researching homelessness in Baltimore – for Man and Woman – taught me a few new facts about the city, but I honestly can’t say that I saw it in a new way. The new way I would like to see it is from the deck of the USS Constellation, the skyline receding into the distance as the ship heads out into the harbor… but I suspect that’s never going to happen. (I promised I’d bring it back!)

JL: Which aspect of Woman’s character do you most relate to? What aspect of Boss’s character do you most relate to?

GS: I think I’ve answered this already: Woman’s fear of change and her desire for stability and Boss’s need to control and prevent change from happening. It took me several drafts, though, to get to the point at which I could answer that question. I demonized them both so much early on, and I had to accept them as necessary parts of the story (and as parts of what I was going through). Whoever said that writing wasn’t therapeutic was foolish; writing that’s only therapeutic, however, is far too small.

JL: What was the most challenging part of writing The Constellation? Which character’s voice was the most difficult to capture?

GS: Finding the right – the most genuine – way for the ship to get out of the harbor was the most difficult challenge. In various drafts, various characters (including a few who are no longer in the play) were on board when it sailed out, but it wasn’t until I realized that the play was about the male characters finding each other and jointly leaving the female characters behind (while the female characters both resisted and facilitated that departure) that the ending finally made sense to me. The most difficult voice to capture was the Boss. I disliked her so much at first, and I had to ease my way into finding her humanity, to understanding that she wasn’t despicable in her own life’s story, and to give her a vision of her own to give voice to throughout the play.

JL: As this interview is taking place, you’re in the middle of rehearsals for The Constellation. What has surprised you about the play?

GS: The play just keeps getting funnier and funnier! (Especially as I chip away at and remove all the unessential bits of language that sometimes bog my early drafts down.) I’m actually always surprised by the humor in my work – people generally think of me as a comedic playwright, I’m led to understand, but I almost never sit down with the intent to write something funny. I’ve been catching myself laughing at my own lines, which I almost never do (and which is probably a testament to this talented cast). It’s great fun.

JL: What next for you as a writer?

GS: I’ve just finished a long run of productions in DC, New York, Chicago, and Los Angeles, and for the first time in a long while my calendar’s somewhat open… which is perfect timing, because I’m about to become a new father, and I know that’s going to claim an impossibly large amount of energy. (At this point, I’m going on complete trust and the promises of some dear playwright friends who’ve also made this transition and managed to keep working.) I have two plays in progress that will compete for whatever attention I do have. Midway is an existential comedy (in the vein of my earlier play Let X) that draws on my time working as a carny. Hot & Cold is a Grand Guignol-style play that juxtaposes the hot zone of a Level IV Biohazard Lab and the cold chill of an ordinary, middle class kitchen on Christmas morning – scientists in terror and a family farce, side-by-side, in an exploration of our national fear of infection. One of them will surely demand to be written first. We’ll see.