D.C. based dramaturg, Hannah J. Hessel has long been one of my favorite people. She's smart, talented, funny, courageous and ambitious. In 2012, when she became the Founder and Creative Trainer at Project Gym, my respect and admiration for her soared. Her entrepreneurial spirit and commitment to the artists in this community provided me with such hope. It is a true comfort to know that there is an affordable space in my community where I can go to for creative inspiration, support and encouragement. Recently, she launched a Strengthen the Project Gym 2013 kickstarter campaign to support a new year of programming. What's truly wonderful about this is that a large part of the funds raised will go to support scholarships for member artists ensuring that everyone who wants to participate can regardless of income. If you're able to contribute or can share this information with others, your investment will go far to support local artists in the D.C. area community. Now, I've been keeping track of Hannah's progress and have been aching to hear about how everything is going. Earlier this week, she gave me a bit of insight into the growth and development of Project Gym, and also shared what she's learned in this first year and her ambitions for all that's ahead. Please enjoy! JACQUELINE LAWTON: What inspired you to establish Project Gym? HANNAH J. HESSEL: Some variation of the Project Gym has lived in the back of my mind for years. It was the time I had in graduate school that allowed me to focus my ideas into a plan. My instructors and fellow classmates at Columbia University School of the Arts were fantastic at listening and challenging my ideas. The time to think about it and write my thesis that explored the possibility made me feel secure in my ideas. When I returned to DC I decided there was no reason not to give it a try. Forum Theatre, where I am the Senior Dramaturg, helped me to put the first beta sessions together. The wonderful artists in DC have been incredibly supportive as I’ve taken steps to turn the Project Gym into a business. JL: What is the guiding philosophy or pedagogy behind the work you do at Project Gym? HH: My MFA thesis title was “Project Gym: Working Out American Theatre.” In it I explored the current state of new work in American theatre and how most of the paths we have for creation aren’t constructed to inspire professional sustainability or experimentation and growth of form. I used a number of ideas from creativity theorists to put together the idea of an environment where artists had the ability to experiment freely without fear of failure, create new points of connection by learning new skills and create a community of artists invested in each others work. What I discovered quickly in my beta sessions was that the reward of these interactions was not exclusive to theatre artists. All artists, and really, all creative people have something to share with each other and can benefit by having a place and time in their life to work on their creativity. JL: Who are your typical participants? How much professional experience or training should they have prior to applying? HH: Part of my discovery is that Project Gym can work for almost everyone. There are three questions I ask in the Project Gym application one is about projects, one about what someone can teach and one about collaboration. The projects give me an idea of the person as a creator – what they are interested in and how they see their work. The teaching is about how they see themselves in a room of other artists, do they see that they can be a valuable member of the community? And the last is the most important. Project Gym members spend most of their time working on other people’s projects, rather than their own, I need to know that they are open to being a collaborator. The majority of the Project Gym members have been professional artists working in a performance related field (playwright, actor, director, dramaturg, performance artist) but I really think that any type of creator (professional or amateur) would have something to add and something to gain. JL: How often do you meet? What is typical session like for the theatre and performance artists? HH: Project Gym meets twice a week. Full-time members aren’t required to attend every session but are encouraged to attend at least once a week. Each three-hour session is structured in the same way:

JL: What is the benefit of working with interdisciplinary artists? HH: I believe that ideas are strengthened when confronted with new thoughts. It is important for artists to see their work through the eyes of someone with a completely different tool set, and it is important for artists to expand their own capabilities. Everything we learn gives us new options for creation. The more we can interact with people who create in a multitude of mediums, the more we are able to expand our own capabilities to create. JL: Project Gym has two levels of membership: Full-time and Drop-in. How are the artists needs met by each format? HH: This is the first year of the two memberships and I’m really excited to see how they work. The biggest difference from the two levels is the amount of attention to the artists’ own projects. Full-time members have the opportunity to teach and lead project time. Part-time members only act as participants and will not have the opportunity to lead. Gym member Jessica Lefkow wrote up descriptions for the Project Gym website about how to choose which level of membership would be right for an artist. I think it’s worth sharing them:

JL: What what the most challenging part of the process in your first year? What did you learn from these experiences? HH: There have been a number of challenges over the past year. The biggest two have been structure and time. I realized half-way through the year that it wasn’t enough to meet once a week, that it is important for the artists to have conversations to develop structure for their sessions within the week. Holding a time-consuming full time job (Audience Enrichment Manager at the Shakespeare Theatre Company) while balancing the conversations and schedule was difficult. I am thrilled though that I’ve hired a second Creative Trainer, the amazing director Jessica Jung, and with her help I think we’ll be able to find a balance that will allow the artists to feel supported – and allow me to focus on my job at work and Project Gym in my off hours. JL: What was the most rewarding part of the process in your first year? HH: The artists! I’ve had 20 amazing artists participate in the past year. Some I knew before they applied and some were completely new to me. It’s been wonderful discovering them as creators and collaborators. The biggest reward for me I think has been one of the biggest rewards for the participants. Talking and playing every week with smart creative people leaves me feeling energized and enthusiastic for the week ahead. JL: What excites you most about this new year ahead? Will any first-year Project Gym members be returning? HH: I am very excited about the steps we are taking forward. As I mentioned, I have hired another Creative Trainer, I am doubling the number of sessions and creating two membership options. I’m a little nervous and very eager to take the Project Gym to this next level. Every session thus far has been a learning experience. I’ve been taking baby steps to keep moving the Gym forward and this year will be no different. This summer we’ll be doing our first weekend intensive and next fall I’m hoping to announce some additional additions. I hope in the following year, I’ll be able to add in some public programming as well so artists can grow their work with audiences. Membership applications for the new semester have just started rolling in and I’ve been happy to see that most of the members from last year will be returning. Some are transferring over to part-time memberships, which makes me happy since I know that even with busy schedules they want to make the Gym part of their lives. I’ve also been really excited to see some folks I don’t know apply! There are plenty of spaces still available so I hope that we will end up with a really diverse group of artists. JL: If folks want to contribute to your fundraiser in order to support and sustain the great work that you're doing, how can we help? HH: Thank you for asking! I am currently running a Strengthen the Project Gym 2013 kickstarter campaign to support the new year of programming. The money I raise mainly goes into scholarships for member artists to ensure that everyone who wants to participate can regardless of income. It’s been five days since the Kickstarter went live and we’ve already made almost 70% of the goal. It’s really exciting to see because everything we make over the goal will be going back to the artists in the form of scholarships and stipends. I hope that people will help the Project Gym keep growing both by giving what they can and, if it sounds like it would be something they’d benefit from, join as members.  Hannah J. Hessel is the Founder and a Creative Trainer at the Project Gym, a space for creative development. She spends her days as the Audience Enrichment Manager at the Shakespeare Theatre Company. At STC, she runs the Creative Conversations discussion series which includes a range of discussion formats including the innovative Twitter Night providing an online conversation before and after a performance. She also oversees the free weekly performance series Happenings at the Harman. Outside of STC, she serves as the Senior Dramaturg at Forum Theatre. She was the Literary Director, Outreach and Education Associate at Theater J. She serves on the board of the Association of Jewish Theater. A graduate of Sarah Lawrence College, she holds an MFA in dramaturgy from Columbia University.

0 Comments

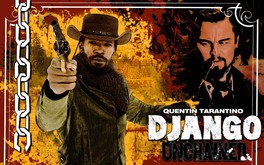

Tonight's the night! Preview performances begin for Constellation Theatre Company's world premiere of Zorro. Break legs everyone! Today, we hear from the brilliant, inspiring and talented co-author and director of Zorro, Eleanor Holdridge. She speaks eloquently about the process of co-writing Zorro and then working to bring this story of adventure, heroism and romance to the stage. Please enjoy!  JACQUELINE LAWTON: What excited you about co-writing and directing Constellation Theatre’s production of Zorro? What made you say yes? ELEANOR HOLDRIDGE: Allison Stockman asked me what I would like to direct for Constellation. I thought about the ambitious mission of the company, as well as it’s size and history and pondered. What could both provide me with a platform for personal experimentation and growth and also fulfill the heart of Constellation’s mission? And so it was not really my director-self who responded to the challenge, but my fledgling writer self. There, in my back pocket, was this Zorro—a play that I’d conceived of several years ago, enlisted the brilliant Janet Allard to be my co-writer, and had been developing in fits and starts over several years. After several developmental workshops, the play was in the place where it was ready for rehearsal and the development that only a rehearsal process can provide. I wanted to be the first director of the piece so that I could hone the arc of the story and integrate the lessons of staging such an adventure into the text itself. And, on top of it all, I’d just worked with the DC actor Danny Gavigan and saw in his wild talent, amazing versatility, his depth and his bearing, something that spoke to both sides of the Diego/Zorro mask. And so, with all these factors in play—when Allison had read the play and wanted to do it, I said yes. Here was the chance to develop the play into what Janet and I hope it will become. JL: Can you talk a bit about your directing process? For instance, what is the first day like for you and the cast? Do you engage in certain exercises or rituals throughout the process? If so, what are they? EH: Over the past few years as a teacher of directing, I have had to analyze how I approach plays and what it is to be a director. What does it mean? What is my responsibility to the audience, to the company and to the community? And it’s tricky because each play is a completely unique synthesis of text, actors, designers, venue and the audience. For each play the aims are different and the tools to forge a production from a text are different. Therefore, the answer the question is “no.” There are no certain exercises or rituals throughout the process. If there are any constants from play to play it is in the constant investigation on what are the goals of the particular play, the work with the design team to find a world that can allow the story and action of the play to live and the creation of a collaborative rehearsal environment where the actors can respond with joy and energy to the text and each other to forge the moment to moment life of the play. JL: What is your approach to directing this play? Is it any different than it would be for a play you did not write? EH: I think the word is compartmentalization. There are times when my director self gets frustrated at my playwright self. There are times when it is the other way around. Thank god for Janet! As a director, I try always to trust the actor’s instincts in response to my worldview of the play and their impulses off of the text and each other—through collaboration we create together an integrated world. As director and co-writer, what can be most tricky are the times when I know exactly what the playwrights’ intent was in creating the stakes and the given circumstances for the characters. And then, in rehearsal, the actor sees something different in underlying objective or motivation. This can create a strange tension within me. And so when the issue comes up, I have to let the original intent go and deal only with the circumstances at hand. It is, as always, not some mythical, idealized character on the page, but the words finding their root within the heart of the individual actor, who turns them into the action of the play. This is what I must strive to honor. JL: What compelled you to co-write Zorro? EH: I can’t remember not knowing Zorro. My dad was born in 1910 (ten years old when the Fairbanks movie came out), and his phrases, stories and tall tales were filled with the purple poetic language of the pulps. I watched the movies and TV series over and over, trying to understand the more innocent childhood of my father’s youth. The myth of Zorro on the screen was always of a simpler time, of an idealistic hero who spurns his own wealth and privilege to help the poor. And, it was Diego’s relationship with his father that drew me most, the need to prove himself and be worthy of his dad’s sense of honor even while he repudiated his father’s acceptance of a corrupt society. As I was trying to figure out who I’d be in the world so, it seemed, was Zorro. Year’s later I was working on an opera in the hills of California, thinking about my father, looking out over the scrubby landscape and suddenly the image of Zorro sprang to mind. I suddenly saw in the myth of Zorro a coming of age story about how we become who we are. I sought to create an origin story for the masked vigilante. How the masks that we all wear give us strength to become what we need to be as well as trapping us within the expectations of others. A story for today. Janet Allard and I had been to graduate school together, worked on countless plays and I have always been a huge fan of her work. There’s a contemporary edgy way she has of conceiving character and turning a phrase, even while she honors and celebrates the best of what it is to be human. And so, I asked her if she’d co-write the piece with me. Wonderfully, she said yes. JL: What was the co-writing process like? EH: It is a blast. Fun. Crazy. Filled with joy. There is both the fun of sitting alone in front of the keyboard inventing of story and arc and dialog, and the wonderful sense of play and collaboration of bouncing those ideas off a partner. I am honored to be working with someone who has such wonderfully quirky sense of the world, who has such humor, wit and linguistic vigor. Janet’s brilliance is inspiring. And, I suspect it will make me a better director at the end of it all.  JL: What was the most challenging part of bringing the story of Zorro to life? Which character’s voice or situation was the most difficult to capture for the stage? EH: In the original pulp, many of the characters, however comic or thrilling, were like cardboard cutouts, as two-dimensional as the cheap pulp paper on which they were printed. For instance, Lolita, Don Diego’s love interest, was presented as simply a prize to be won, not a living, breathing girl struggling to find her own voice within a society that marginalizes women. And so we strove to forge her into a heroine for today. Also, the characters of Ramon and Gonzales seemed to come off in the pulp as simply an arch-villain and buffoon. For all these secondary characters there was action, but not a lot of backstory or depth. And so as Janet and I continued to send drafts to each other we undertook various passes at the script to imbed stakes and complicated history and objectives into the scenes. Janet took on Gonzales, imagining him as the guy who used to protect the weak from bullies on the schoolyard, and then joins the military service only to find out that he is forced to become a bully himself, trapped in the job as he needs to support his family. I took on the character of Ramon, imagining him not just as a villain, but as a self-made man who sees in the power-hungry Governor a father figure, who carries deep prejudices against the privileged class and who loves so deeply and obsessively that it threatens to destroy all around him. As we continue to work on the play, it is our aim to bring forth characters of complexity that, in the midst of a hero story, grapple with a complicated world.  JL: Johnston McCulley created Zorro in 1919 as part pulp-fiction series. What makes this story of romance, heroism and adventure relevant to audiences? EH: Johnston McCulley created a simple world of good versus evil—a tale of bravery and the daring of one man in the face of an unexamined evil. Today our country’s all grown up. We examine the forces behind the evil and the good. We live in a world of incredible complexity even while we long for stories of heroes who stand against all odds to make the world a better place. Why? I think that at the core of the entertainment is our desire to be inspired. It is easy to accept the circumstances handed to us by our parents, our government, and our society and to say, “well that’s just how things are.” But this is an origin story in which we celebrate the individual’s choice to act and make a difference. In witnessing a reluctant hero who sees a wrong, faces his individual responsibility, makes the choice to right those wrongs and bravely faces the consequences of his actions, I believe we can be inspired to do so ourselves. JL: What next for you as a director? Where can we follow your work? EH: Come see Yasmena Reza’s God of Carnage at Everyman Theatre in Baltimore running March 13 to April 7th. And I may try my hand at some more adaptation.  Director, Eleanor Holdridge has Off-Broadway productions that include Steve & Idi, (Rattlestick Playwrights Theatre), Cycling Past The Matterhorn(Clurman Theatre), The Imaginary Invalid, and Mary Stuart (Pearl Theatre Company). Regional credits include Gee’s Bend (Arden Theatre); Hamlet, Midsummer Night's Dream, As You Like It, Lettice And Lovage, The Tempest, Twelfth Night, Taming Of The Shrew(Shakespeare & Company). The Crucible (Perseverance Theatre), Educating Rita, Noises Off and Art (Triad Stage), Julius Caesar and Macbeth (Milwaukee Shakespeare), Two Gentlemen Of Verona (Alabama Shakespeare), Midsummer Night's Dream (Shakespeare St. Louis), Henry V (Shakespeare on the Sound), Betrayal (Portland Stage), and Lion In Winter (Northern Stage). Her DC area productions include Double Indemnity(Roundhouse Theatre),The Gaming Table (Folger) Pygmalion (Everyman Theatre);Something You Did and Body Awareness (Theatre J); and Much Ado About Nothing(Taffety Punk). Eleanor has been as Artistic Director for the Red Heel Theatre Company, Resident Assistant Director at the Shakespeare Theatre and Resident Director at New Dramatists. She has worked at the Yale School of Drama, NYU and the Juilliard School and currently heads the Directing Department at Catholic University. She holds an MFA from Yale School of Drama. Eleanor’s upcoming projects this season are Zorroat Constellation Theatre, and God of Carnage at Everyman Theatre.  PRODUCTION DETAILS WHO: Constellation Theatre Company WHAT: Zorro by Janet Allard and Eleanor Holdridge. Directed by Eleanor Holdridge WHERE: Source Theatre 1835 14th St. NW WHEN: January 17- February 17, 2013. OTHER: Audiences aged 10 and up. A parent or guardian should accompany any child under 13. WEBSITE: www.ConstellationTheatre.org Constellation Theatre Company Mission: Constellation Theatre Company’s mission is to spark the curiosity and imagination of the people of Greater Washington, DC by bringing stories to life from all over the world. Visual spectacle, music and movement unite with an exuberant acting ensemble to create an exhilarating entertainment experience. We're only one day away from Constellation Theatre Company's world premiere of Zorro! As you know by now, one of my favorite things to do is meet new playwrights and learn all about their writing process and artistic journeys. Playwright and co-author of Zorro, Janet Allard, was gracious enough to share her experiences with us here. She also gives us more insight into the world of Zorro. Please enjoy!  JACQUELINE LAWTON: Why did you decide to get into theatre? Was there someone or a particular show that inspired you? JANET ALLARD: Alice in Wonderland maybe? My aunt and uncle were Broadway dancers so we always had cast albums of Broadway musicals on the record player (now I sound really old). I daydreamed all the time. Then, somehow I found acting and through that writing. I won the Very Special Arts Playwright Award at the Kennedy Center and the Young Playwrights Festival in NY. After two professional productions at a young age I was hooked. JL: Next, tell me a little bit about your writing process. Do you have any writing rituals? Do you write in the same place or in different places? JA: I wish I was one of those people who wrote for a few hours each day, but I find that I will not write for a month or two and then write day and night to complete a draft. I like Deadlines. Pressure fuels me. So does collaboration. I’m not much for routine so I write different places – anywhere, anytime when there is a play to write I can just drown out the world and write. JL: Describe for me all the sensations you had the first time you had one of your plays produced and you sat in the audience while it was performed...what was different about the characters you created? How much input did you have in the directing of that work? JA: The sensations I had the first time I saw my work done are the sensations I still have. A sense of astonishment that what I wrote is up there before an audience with actors speaking the words that began in my head. I always feel nervous, there’s a sense that what was very personal is now becoming public. It’s very thrilling—and at the same time I’m just watching, not actively participating in the moment – the way an actor does, so there is a feeling of helplessness – which is also kind of thrilling. And I’m always sort of making little adjustments in my mind – what I could add or subtract or do differently. The best is when I forget to do that and just get lost in the story or am surprised and moved by the actors’ performances. JL: What do you hope to convey in the plays that you create--what are they about? What sorts of people, situation, circumstances, do you like to write about? JA: Very different things. I tend to write about people searching for their identity – outsiders trying to define their place in the world. Zorro really fits into this.  JL: What compelled you to co-write Zorro? JA: Eleanor came to me with the idea and I love collaborating with her – and once I read the original pulp novel I was drawn into the Diego/Zorro search for identity – and how he gets trapped in his own superhero mask. With Eleanor as co-writer I became interested in our vision to write a “creation of Zorro” story – what causes Diego to dawn the superhero mask. The father/son story I find compelling and also the politics – which resonate in today’s world. JL: What was the co-writing process like? JA: We work very well together. We would take turns on scenes or sometimes write together. If I was at a loss for what should happen in a certain moment, Eleanor had ideas and vice versa. It’s been a process of discovering things together Johnston McCulley created Zorro in 1919 as part pulp-fiction series.  JL: What makes this story of romance, heroism and adventure relevant to audiences? JA: Super-hero stories are timeless. They tap into a very deep-seeded need we all have for justice and greatness as well as our fear of failing our world, our families, our romantic partners etc. The core actions of Zorro – trying to right wrongs, trying to make the world a better place, trying to win the love of the girl, trying to win his father’s approval are timeless. JL: What advice do you have for up-and-coming playwrights? JA: Write and keep writing. And meet people. Lots of people you love to work with. And persuade them (somehow) to do your plays. JL: What next for you as a writer and where can we follow your work? JA: I’m in the final stages of getting the rights to make a musical stage adaptation of Jon Krakauer’s book Into the Wild about Christopher McCandless. It’s an amazing story – so that’s the next adventure. A few of my plays are published by Playscripts Inc. and Samuel French and I’m a member of the Playwrights Center in Minneapolis– that’s a good way to follow me.  Janet Allard's recent works include Pool Boy at Barrington Stage, Vrooommm! A NASComedy published by Samuel French, Speed Date, Incognito, Loyal and Untold Crimes of Insomniacs, published by Playscripts, Inc. Her musical The Unknown: A Silent Movie Musical won a Jonathan Larson Award with P73 Productions and appeared at NYMF. Her work has been seen at The Guthrie Lab, The Kennedy Center, Mixed Blood, Playwrights Horizons, Yale Rep, The Yale Cabaret, The Women’s Project, Perseverance Theatre, Joe’s Pub, Barrington Stage, with P73 Productions, and Internationally in Ireland, England, Greece, Australia and New Zealand. She is a Fulbright Fellow, has an M.F.A in Playwriting from the Yale School of Drama, has studied at the NYU Musical Theatre Writing program and teaches at University of North Carolina at Greensboro.  PRODUCTION DETAILS WHO: Constellation Theatre Company WHAT: Zorro by Janet Allard and Eleanor Holdridge. Directed by Eleanor Holdridge WHERE: Source Theatre 1835 14th St. NW WHEN: January 17- February 17, 2013. OTHER: Audiences aged 10 and up. A parent or guardian should accompany any child under 13. WEBSITE: www.ConstellationTheatre.org Constellation Theatre Company Mission: Constellation Theatre Company’s mission is to spark the curiosity and imagination of the people of Greater Washington, DC by bringing stories to life from all over the world. Visual spectacle, music and movement unite with an exuberant acting ensemble to create an exhilarating entertainment experience. We're just two days away from the world premiere production of Zorro! I got a sneak peek at a few rehearsal photos and can tell you that audiences are in for a real treat. I'm going to share a few photos with you tomorrow along with the playwrights interviews. For now, however, please enjoy this interview with Constellation Theatre Company's Artistic Director, Allison Stockman.  JACQUELINE LAWTON: What excited you about programming the world premiere of Zorro in Constellation Theatre’s season this year? ALLISON STOCKMAN: I first approached Eleanor to direct for Constellation, and she proposed this world premiere of Zorro. I love the story – who doesn’t? Adventure, romance, passion, swashbuckling – Zorro has it all! Zorro is also a great fit with Constellation’s mission. Zorro is an epic, timeless legend with opportunities for visual spectacle, original music and heightened movement. It’s a strong ensemble piece about the importance of standing up for justice for all. Janet and Eleanor have also written a script with beautiful language, poetic imagery and a healthy dose of humor. JL: Zorro is co-written and directed by Janet Allard and Eleanor Holdridge. Why was it important to have a female perspective on a male driven story? AS: Janet and Eleanor’s female perspective on the story gives it two advantages. First, Zorro is a romantic hero, dashing and clever, while Diego is smart, but shy and still finding himself. The playwrights have balanced his charming appeal with emotional vulnerability in a way that gives the character great depth. Second, the character of Lolita is often downplayed and portrayed as a one-dimensional ingénue who only serves as the love interest for men. In Janet and Eleanor’s version, Lolita is political and fiery. She has a provocative voice and is herself going on a journey of self-discovery with a strong arc. JL: Johnston McCulley created Zorro in 1919 as part pulp-fiction series. What makes this story of romance, heroism and adventure relevant to audiences? AS: The entertainment aspects of Zorro – the double identity, mystery, swashbuckling, romance – thrill people today just as they did in 1919, and as they did thousands of years ago. Kissing and fighting never gets old. This version of Zorro also focuses on Diego’s dilemma about what to do when faced with corruption and violence. He takes the risk of standing up for what he knows is right in the face of danger, political oppression and social pressure. This challenge of doing the right thing, even when it is difficult and frightening, is just as relevant today as it was nearly a hundred years ago. Watching the politics in Washington and in the world always reminds me of this tension. JL: You’re billing this adaptation as a coming of age story about self-discovery and the courage needed to seek justice for all. What can audiences learn from Diego’s passion, zeal and sense of duty? AS: Hopefully Zorro inspires people to think for themselves and to have the courage of their convictions. On a basic human level, Zorro is also about living your own personal truth and embracing the challenges of self-discovery and transformation. We choose who we are by what we say and what we do. We often tend towards what is easy, but Zorro follows his inner desire to be brave, passionate and just. JL: If there is one thing you want audiences to walk away knowing or thinking about after experiencing Zorro, what would that be? AS: I hope the audience walks away from Zorro having had a wonderful time, having thoroughly enjoyed the experience. I hope it might spark conversation about how this version is different from other Zorros and why this story continues to appeal to people 100 years later. Perhaps people will enjoy thinking about all of the stories and super heroes that Zorro has inspired. I hope it also encourages people to live their own lives passionately, taking the chance to fall in love and being courageous enough to become active in their own community.  Allison Arkell Stockman is the Founding Artistic Director of Constellation Theatre Company, which performs at Source, 1835 14th St. NW. She has directed 16 of their productions including Metamorphoses, The Ramayana, The Green Bird, Taking Steps, Women Beware Women, Three Sisters, A Flea in Her Ear and The Arabian Nights. She will direct Gilgamesh this coming spring. Locally, Allison has served as an Assistant Director at the Folger Theatre and Shakespeare Theatre Company. She has directed readings and workshops for Theater J and the Kennedy Center. A Drama League Directing Fellow and a member of the Lincoln Center Theater Directors Lab, Allison holds an MFA in Directing from Carnegie Mellon School of Drama and a BA in Comparative Religion from Princeton.  PRODUCTION DETAILS WHO: Constellation Theatre Company WHAT: Zorro by Janet Allard and Eleanor Holdridge. Directed by Eleanor Holdridge WHERE: Source Theatre 1835 14th St. NW WHEN: January 17- February 17, 2013. OTHER: Audiences aged 10 and up. A parent or guardian should accompany any child under 13. WEBSITE: www.ConstellationTheatre.org Constellation Theatre Company Mission: Constellation Theatre Company’s mission is to spark the curiosity and imagination of the people of Greater Washington, DC by bringing stories to life from all over the world. Visual spectacle, music and movement unite with an exuberant acting ensemble to create an exhilarating entertainment experience.  Bless my ever-resilient heart, I'm a hopeless romantic and a complete fool when it comes to love. The practicality of the Capricorn is completely lost on me. I also have a mischievous sense of adventure. As a child, I devoured maps and dreamed of all the places that I would one day go. During grad school, I finally got to travel and spent my summers abroad in Europe and Australia. What's more, my favorite heroes are those who risk life and limb in unrelenting pursuits of justice, freedom, truth and equality. And my favorite characters to write are soldiers for their sense of duty, code of loyalty and honor and their ardent love of country. With all of that, it's no wonder that Zorro is one of my favorite fictional characters. I'm so excited to see Constellation Theatre Company's upcoming world premiere production of Zorro written by Janet Allard and Eleanor Holdridge, who also serves as director. It opens to Pay-What-You-Can previews on Thursday, January 17th and runs to February 17, 2013. I'm going on Saturday and can hardly wait! Over the next few days, I'm going to share interviews from Constellation Theatre Company's Allison Stockman and co-authors Janet Allard and Eleanor Holdridge, all of whom speak honestly, passionately and eloquently about their admiration for Zorro, the significance of this beautiful new play, and what it took to bring this world premiere to one of D.C.'s finest stages. For now, here's more information on the show and how you can purchase tickets: Mystery, Romance, Adventure & Swashbuckling!! Zorro, the masked avenger, is born when quiet, bookish Diego must find a way to fight corruption and injustice in this swashbuckling adventure. This World Premiere reframes the pulp drama as a coming of age story about self-discovery and the courage needed to seek justice for all. It is a world of high romance and adventure, where good vanquishes evil, and wrongs are righted with three signature swipes of a sword.  Danny Gavigan as Zorro. Photo by Andrew Propp. The history of Zorro has captivated our collective imagination for nearly 100 years. Darting thrice with his rapier, the mark of the "Z" has been the calling card of the world's most recognized masked highwayman. At once romantic, passionate and righteous, Zorro has become an intergenerational, cross-cultural icon. Immortalized by a wide span of genres, the man in the black mask continues to inspire with tales of his great adventures. Zorro made his first appearance in the August 9, 1919 edition of the pulp-fiction journal All-Story Weekly in The Curse of Capistrano, created by freelance writer and first generation Irishman, Johnston McCulley. No sooner did Zorro's legend begin on the written page did it spread to the silver screen. A year after The Curse of Capistrano was issued, Douglas Fairbanks Sr. starred in the 1920 silent film The Mark of Zorro as the fox and his foppish alter ego, Don Diego de la Vega. Since the 1920's, there have been fifteen Zorro movies made in the United States, and over thirty films internationally. The Zorro Disney television series, starring Guy Williams, debuted in 1957 and had seventy-eight episodes and four one-hour specials. The rudiments of the Zorro lore - a masked hero who fights for the oppressed - also inspired a host of dual identity avengers, including the Phantom, the Lone Ranger, the Green Hornet, Superman and Batman. In many ways, Zorro was the first modern super-hero. Eleanor Holdridge teamed up with fellow Yale School of Drama alumna Janet Allard to bring the story of Zorro to the stage. Holdridge’s directing work has been seen at many Washington area theatres including: Folger Theatre (The Gaming Table), Theatre J (Body Awareness), Round House Theatre (Double Indemnity) and Taffety Punk (Much Ado About Nothing). Allard's work has been seen at The Guthrie Lab, The Kennedy Center, Mixed Blood, Playwrights Horizons, Yale Rep, The Yale Cabaret, The Women's Project and Productions, Perseverance Theatre, The House Of Candles, and Access Theater in New York City, as well as internationally in Ireland, England, Greece, and New Zealand. Holdridge’s passion for Zorro dates back to childhood. She remembers, “My dad was born in 1910 and was ten years old when the Fairbanks movie came out. His phrases, stories and tall tales were filled with the purple poetic language of the pulps. I watched the movies and TV series over and over, trying to understand the more innocent childhood of my father’s youth… As I was trying to figure out who I’d be in the world so, it seemed, was Zorro.”

Ensemble: Vanessa Bradchulis, Oscar Ceville, Danny Gavigan*, Carlos Juan Gonzalez*, Jim Jorgensen, Michael Kramer*, Stephanie LaVardera, Carlos Saldaña, Andrés Talero. *Member, Actors’ Equity Association Design and Production: A.J. Guban (Set), Kendrai Rai (Costumes), Nancy Shertler (Lights), Mariano Vales (Composer), Behzad Habibzai (Sound Designer), Casey Kaleba (Fight Choreographer), Melissa Flaim (Dialect Coach), Taylor Hitaffer (Dramaturg), Cheryl Gnerlich (Stage Manager), Kevin Laughon (Props Design), Jason Krznarich (Technical Director), Jeny Hall (Master Electrician), Audience Relations Coordinator (Lindsey Ruehl). PRODUCTION DETAILS WHO: Constellation Theatre Company WHAT: Zorro by Janet Allard and Eleanor Holdridge. Directed by Eleanor Holdridge WHERE: Source Theatre 1835 14th St. NW WHEN: January 17- February 17, 2013. OTHER: Audiences aged 10 and up. A parent or guardian should accompany any child under 13. WEBSITE: www.ConstellationTheatre.org  Next week, from Monday, January 14 to Wednesday, January 16, Arena Stage's The Kogod Cradle Series will feature three workshop performances/open rehearsals of The Age of Innocence, a new adaptation of Edith Whartons' classic novel by resident playwright Karen Zacarías. In this workshop/open rehearsal format, our audience participation is to development of Karen's new play still in process. What's more, there will be post-workshop discussions with Karen and New Play Institute Dramaturg Jocelyn Clarke. All tickets are $10 and can be purchased here. You'll want to hurry, because tickets are selling out fast! About the Play Newland Archer couldn't be more pleased with his recent engagement to the beautiful debutante May Welland. However, his world is thrown upside down by the sensational arrival of May's cousin, Countess Ellen Olenska. A cast of favorite DC actors, including Michael Russotto and Tonya Beckman Ross, help bring Zacarías’ new adaptation of Edith Wharton’s American masterpiece to the stage, exploring love, loss and longing through the lens of New York’s social elite. I'm enamored with the novel and can hardly wait to see Karen's beautiful work. I'll be attending the performance on Wednesday with friends. I became even more excited after speaking with Karen about her new play development process and her own passion for the Edith Wharton's Pulitzer Prize winning novel. Here's our conversation:  Jacqueline Lawton: What is it about writing plays that draws you…as opposed to writing poetry, songs, or fiction? KAREN ZACARIAS: I love all forms of writing ... including songs, poetry and fiction ... but playmaking is my passion. I love the interaction of characters both on the page and on the stage. I am fascinated by the interpretation, subtext, and "fullness" of dialogue. JL: What inspired you to adapt Edith Wharton's Age of Innocence? KZ: I've loved the book for years, so much that I used an except of it in my comedy THE BOOK CLUB PLAY. At one point, while we were rehearsing the scene and I was talking about the essence of the book, Molly Smith turned to me and said, "I've never seen a theatrical treatment of The Age of Innocence. You are the person who should adapt that book for the stage." It was the right encouragement at the right time. JL: What has been the most challenging part of the adaptation process? Which character’s voice or situation was the most difficult to capture? KZ: To me, the true beauty of The Age of Innocence goes beyond the plot and lies in the lush and eviscerating description of human nature and love ensnared by habit and societal rules. The compelling "plot" of the book is of deep yearning and inaction; but the real "story" is of a man waking up to the decisions he is constantly making by choosing to be part of a community. The theatricality of the book lives in the dynamic details and wry wit of Edith Wharton's observations. The only way I could find to really honor Wharton's work, was to make sure her voice stayed front and center; that meant I decided to choose to break certain standard playwriting "rules". Capturing Edith Wharton's voice and building the atmosphere of the time has been the greatest challenge and reward by far... and a personal act of questioning certain playwriting "standards."  JL: Written in 1920 and set in upper-class New York City in the 1870s, Edith Wharton won the Pulitzer Prize for this novel. What makes this bold, passionate and beautiful novel relevant for audiences today? KZ: THE AGE OF INNOCENCE is about a society in transition, re-defining social mores and attitudes about marriage, while reeling from a NYC banking scandal...which could be a description of the 1870's or... of 2013. Although so many of the particular rules and constraints of the novel don't exist for us today, we have built a whole series of new ones for our generation (write a Facebook message in capital letters at your own peril) In fact, sometimes it feels like we have done a 360- going from the tragedy of an "inarticulate lifetime" in the 1870's to the phenomenon of what I call " constant commentary"- and I wonder if either scenario allows for self-reflection or examination of who we are and why we do what we do. Meeting Countess Ellen Olenska forces Newland Archer to question things he always assumed were answered; reading Edith Wharton does the same for me-it makes me question my everyday choices and forces me to examine why I live the way I do-which is vital...and uncomfortable and very easy to avoid. Last week, there was a great article in the Washington Post by Philip Kennicot about the web's fascination and acceptance of ugly images in our time. In it he states "Something is happening, some kind of cleft in the moral life that is being widened, channeled out by the torrent of small images that invite us to enjoy suffering or think ill of others. If all of this is widening the canyon between our better and worse selves, on which side of the chasm will we end up standing?" It is a question that Edith asks herself and we now, over a hundred years later ask ourselves: Is our Age of Innocence over? JL: Why was it important for the production of Age of Innocence to be a part of Arena Stage’s Cradle Series? How has this experience benefited the growth and development of the piece? KZ: Arena Stage, my dramaturg Jocelyn Clark, and I are approaching this new adaptation in a very dynamic way- the hope is not just to create dialogue around the story of THE AGE OF INNOCENCE but also create a conversation around play development. Instead of spending the time at the table with my script- we are choosing to physically "build the play" from the first day with eleven actors, sound, music, movement, eleven chairs and two tables. The three presentations at the Kogod (Jan 14,15,16) will be in essence open rehearsals of a run-thru of the whole play- a play under construction. It will be a 3 dimensional presentation of the theatricality embedded in the script...instead of the standard of actors reading words. I think revisiting the idea of "reading and play development" is at the core of the Arena Stage residencies- and what theatrical experimentation, and growth are all about. A playwright creates a script but a PLAY lives in the actors and grows with an audience. All need to be a dynamic part of the process. I'm very excited and a little bit scared of opening up the process and product simultaneously with an audience. It will be an adventure for all involved. About the Cradle SeriesThe Kogod Cradle Series supports the exploration and development of new and emerging work in the Kogod Cradle with visiting companies, artists and ensembles. Focusing on the development of new plays and devised work by artists from throughout Greater Washington and around the country, this series of readings and workshops invites artists and audiences to explore the development process and allows artists and audiences to participate who otherwise might not be able to easily access Arena Stage. This series also supports the development of local artists and seeks to further develop our local talent pool of playwrights, actors and directors here in Greater Washington.

As I mentioned in my previous post, I reach out to my friend and fellow playwright, Kia Corthron to see if she would contribute to my ongoing blog series about Diversity and Inclusion, which can be read here and here. She was excited about the series and wanted to share an article that she had written for the Dramatist Guild's The Dramatist magazine called, The Ethics of Ethnic, which brilliantly addresses the issue of artistic authority. In it, Kia asks colleagues to participate because she felt "there were as many different answers to my questions about artistic authority as there were playwrights." In Part Three of the Artistic Authority Blog Series, we will be hearing from playwrights Dael Orlandersmith, J.T. Rogers, Najla Saïd, Betty Shamieh, Stew, Caridad Svich, Naomi Wallace, Allison Warden, and Rhiana Yazzie. Of course, this article was originally printed in the Sept/Oct 2010 issue of The Dramatist, the journal of the Dramatist Guild of America, Inc. Please enjoy!  DAEL ORLANDERSMITH The role of art / any art form means that we as the writers have to be mental and emotional travelers. Many groups interest me and that is UNIVERSAL, and I feel UNIVERSALISM is a good thing / The problem arises when someone writes about another culture/race/ethnic group and tries to speak FOR that group to that audience / as opposed to speaking TO an audience and by speaking FOR that group / They end up stereotyping. People are multifaceted and whatever group(s) one is drawn to / it is MANDATORY to find the HUMAN BEING(S) within that culture and look at the INDIVIDUAL(S)’ story(ies) within the story the writer is telling. There is a writer/performer who has a made a living playing characters outside of that writer/performer's own race / There is nothing wrong with this but as stated above, this person tries to SPEAK FOR the races and by doing so not only does this person infantilize people / this person shows his/her bias. The work has sound bites but the people are not fully realized. For many people who do not step out of their own comfort zone / this person's work is seen as “DARING.” In ref to the people that are delineated in the work the ACTUAL GROUPS themselves / it's patronizing and non-informative. I wrote a play a few years ago called Rawboys which was about an Irish family in south London. The play was beset with many problems and one critic opened her VERY racist review by saying “there are enough self-hating Irish / they don't need a BLACK WOMAN to jump on the cudgel for them.” People HERE in the States thought the language of the play was too much. Ironically I did a reading of it in Ireland where the IRISH thought it fine and many in the audience told me that I wrote “good stuff” and nailed the colloquialisms. I do find as a woman and as a black woman writer the rules are not the same as it is for white writers male and female. Whites have written about ALL people of color but yet when the reverse happens / indeed the response is NOT the same. I write about ALL kinds of subjects and all kinds of people - not just black people. After writing Yellowman I think the expectation was to keep writing a certain kind of way. I cannot / will not do that / To do that means NOT to travel / learn – it means death to a writer. Dael Orlandersmith is a performer/writer of plays and poetry. Her play Yellowman was a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize. She lives in New York City.  J. T. ROGERS Playwriting is in the details. So when I write a character who is a Rwandan pediatrician living in Kigali, or create both a devout Pashtun Afghan mujahideen commander fighting against the Soviets and the KGB officer trying to stop him, I have to make sure I know what I'm talking about. After doing research, I make up my story, and then – most crucially – before I send the play out into the world, I have it vetted by people who are as close to those I've created as possible. In the first case, I poured over the play with a Rwandan doctor who had lived through the Genocide of 1993; in the latter, I spent hours running things by both former intelligence officers and Afghan civilians who were involved with the Afghan-Soviet War. In every case, the people I talk with are generous with their time and their comments; their criticism is invaluable. But the one thing these non-theater folk never ask is, Who do you think you are to write about me? In fact (so far, mind you) the universal response has been the opposite: I'm so glad you're writing about this and taking the time to try and do it right. The story itself quickly becomes the subject of our conversation. Because an exciting, thought-provoking tale is something that interests everyone. J. T. Rogers is the author of The Overwhelming, set in Kigali, Rwanda, which has been produced in London, New York, and around the world. His new play, Blood and Gifts, set in Pakistan and Afghanistan, premieres at London's National Theatre in September. He lives in Brooklyn, New York.  NAJLA SAID One of the greatest challenges that a writer must face is that of writing from the perspective of another human being. The character may be fictitious or real, the same sex, sexual orientation, race, age, social class, ethnicity as the writer – or not. In my opinion, "ethnicity" is in the same category as all of the others I've mentioned. The artist's job is to create realistic characters whose truths and experiences are believable, period. This can be tricky business, especially if the writer sets out to tell the story of someone of a marginalized or underrepresented, misunderstood community. While I was writing my solo play, Palestine, about growing up Arab-American, a friend published his first novel. It was a first-person account of the harrowing childhood of a young African-American boy in the projects. When he first approached agents and editors with his manuscript, more than one person suspected him of not being the author. He was good looking, clearly from an upper-middle class background, and white. It seemed impossible that he could have written the story so delicately; so precisely and believably. My friend’s experience got me thinking about the subject of who is "allowed" to write about what and why. My play was personal, and so even though I was bold in voicing my “controversial” politics and frank in my descriptions of the apartheid I'd seen in Palestine, I was met with very little opposition. Many people who disagreed with my politics were able to connect with my experience, and listen to my point of view. But I wondered what would have happened if I had pretended the story was fiction? People might have said, “How could the daughter of a famous outspoken Palestinian have grown up speaking Yiddish and hanging out with Jewish people in NYC? That’s ridiculous! And she says her Arab family was Quaker and Baptist? That’s insane and far-fetched!!” I myself have sat in the audience of many a play about the Palestinian/Israeli conflict and grumbled about how the author has "no idea" what he or she is talking about because of the subtle inconsistencies and implausibility of the plot. But I have also sat in the audiences of such plays and been amazed to discover they weren’t written by an Arab. I think the issue is one of good, honest, thorough WORK, of talent, of sensitivity, of the playwright doing his/her homework and being open to critical suggestions as the draft is perfected. But the writer should be on top of all of these things whether she is writing about herself or about a transsexual from the farthest point on the earth. The only real "authority" there is, is the truth, and it is our job as writers to find the truth within the stories and the characters we create, and tell it. Najla Saïd is an actor and writer whose play Palestine premiered in New York in 2010. She lives in New York City and is currently working on a memoir.  BETTY SHAMIEH It is essential to remember that when we are talking about race, what we are often talking around is the other “r” word. Resources. I don’t think that many artists of color would care if white writers depict characters of color in their plays – nor would white artists complain that they don’t have a shot at many grants – if more people felt that the economic realities of American theatre were not structured in a way that was unfairly stacked against them. I believe playwrights must have the freedom and space to portray whomever they wish. In fact, I feel it is profoundly important for us to imagine those who are different from ourselves, and I developed a workshop series called “Writing the Other” for American writers of Arab and Jewish descent to write characters with each other’s perspectives as part of an NEA grant. The real problem in American theatre is the content of the work that is being produced, not the color of the writers. We are living in a time of war. Currently, the plays that deal with the most pressing and hot-button issues of our era that receive productions on major American stages are primarily those that tend to reinforce stereotypes and, in the case of Middle Eastern characters, sound the drumbeats of war, despite the intentions of well-meaning and oftentimes left-leaning writers. If American stages were filled with gut-wrenching stories about how brutally and inhumanely the Vietcong leadership acted towards their own people during the Vietnam War, would that be neutral? So, is it neutral that the bulk of the American plays or British imports that get produced about the Middle East happen to highlight the horrors of living under the Taliban or Saddam’s regime? What would it mean if those same plays were instead set in Saudi Arabia or Egypt, countries which are currently our allies? Where are the stories that reflect the reality that the vast majority of Middle Easterners are not victims or perpetrators of unimaginably horrific violence, but simply human beings whose lives and concerns are not that different from those in the audience? Arab-American artists in every field, including myself, are currently primarily working in Europe. But, provocative white writers like Wallace Shawn have found it difficult to be produced in America as well. Why does that matter? Because we American playwrights are engaged in a cultural conversation. We are continually being influenced by and responding to the work of our peers. If our community of artists is not being exposed to the most challenging American voices of our time, we are all the poorer for it. Currently a playwright-in-residence at Het Zuidelijk Toneel of Holland, Betty Shamieh’s recent productions in translation include Again and Against (Playhouse Teater, Sweden), The Black Eyed (Theater Fournos, Greece), and Territories (European Union Capital of Culture Festival). She lives in New York City.  STEW I think artists have the authority to write about anything they want whether they know what the hell they are talking about or not. My favorite artists don’t attempt to frame reality as it “is” but rather as they see it and receive it. There should be no Art Laws. I would not want to live in a world where an artist had to be an expert on a race before he could depict that race in a work of art. For in that world, only anthropologists would be allowed to make plays. I think American playwrights should be ENCOURAGED to write IGNORANTLY about races beyond theirs. Screw the Art Police. For the uninformed view can be just as enlightening, compelling, valid and truthful as the so-called “informed” view. I even think plays written “outside” of one’s race could help race relations and raise consciousness levels (cue orchestra swell). Because what is just as enlightening as how a group views itself is how said group is viewed by so-called “outsiders.” Even the “wrong” “ill-informed” view is still a kind of truth. And that is why it is feared. Besides, we have reached a stage where minorities are both capable of and fully willing to create minstrelsy all by themselves without the help or coercion of “the white man” so at this point all bets are off. The European characters in Passing Strange were for the most part caricatures. I found this a perfectly valid way of depicting them and the kid’s experience of them in Europe. I don’t think caricatures strip characters of their humanity nor their truth. My approach mirrored the Youth’s tendency to “other” residents of whatever foreign environment he happened to be in. This is natural and it would be lame PC wrongness to pretend that we are not taken and enchanted by surfaces, by differences and by exoticness, before we get to the depth of the foreignness we are encountering, if we ever do. And Youth does eventually get beneath the surface of these individuals. I was also comfortable with caricatures because the kinds of people I was drawing (artists, radicals, etc) tend to “characterturize” themselves, if you will, before you even have the chance to do it to them. They very consciously want to live and be perceived by their ideals, which they wear on the surface of their bodies in their language and in their coded uniforms of cool. I prepared myself for accusations of taking the same reductive, stereotypical approach to white Europeans as all the white writers throughout the ages had towards people of color: using them primarily as conduits for humor. It might be a mistake to think that depth automatically tells us more about a character than the surface. The surface can be more telling than what is beneath it. In other words, there is a depth within the surface. And I admit I was thrilled to have both Germans and Dutch people tell me that I nailed the people I was depicting. Stew, resident of Berlin/Brooklyn, father of two, and co-creator of Passing Strange is still trying to figure out how he won the Tony for Best Book of a Musical.  CARIDAD SVICH As a writer, I believe you're almost honor-bound to write outside your ethnicity, sex, gender and history or else why write at all? I always tell younger writers Write what you don't know, explore and write from your fears, wounds, areas of doubt. We go to the theatre to go outside ourselves, to embrace Others and others, to understand humanity a little better, and be startled and amused and sobered up/awakened to truths. Where does authority come from? It comes from looking at a subject straight in its heart and speaking his or her truths as profoundly as the imagination allows, and from this exploration discovering the confidence of translating the subject's experience to the spatial and temporal planes of the stage. I've written characters older, younger, transgender, bisexual, male, female, Latina/o, black, Anglo, Cuban, Spanish, Chilean, animal, or robot, in this time frame and in times long ago, etc. The fact that I'm of Cuban-Argentine-Spanish-Croatian background enters into everything I write. You can never escape who you are. Know where and who you're from, and you'll know, then, where you can go...and how far you can push yourself as an artist and thinker and observer and chronicler and poet of the human condition. The negative experiences have nearly always had to do with portrayals that are patronizing, victimizing, class-based, and/or rooted in stereotypes. I don't think, however, that writers within my multiple ethnicity are exempt from writing negatively about characters. I think it's too easy to castigate and blame in the ethnicity/identity-stakes game of authorship. An untruthful character, and of course this too depends on what the form and genre of the play is, will strike me negatively regardless of who writes it. One of my first major plays Any Place But Here, which is about two couples struggling to make ends and love meet in an economically-depressed northeastern town, was produced, in its first version, at INTAR in New York City directed by George Ferencz. (It was later produced at Theater for the New City under Maria Irene Fornes' direction in its revised version.) I never say in the script what the characters' ethnicities are. During the casting process we called in as open and inclusive a line-up of actors as one could think of. In the end, due to the many vagaries of casting, the original cast was Jessica Hecht, Peter McCabe, Jim Abele and Mimi Quinn. All wonderful actors but not one of them Latino/a. I know that the play caused some degree of alienation within the community for the play to be produced at INTAR. And it saddened me. Not because my ego was wounded, but rather because I wrote the play to say a little something about the difficulty people have communicating with each other and sustaining lives with each other when they feel trapped by circumstances of poverty, mis-education, loneliness and on the edge of emotional catastrophe. Can't we just talk to each other and see what little light we can glean from each others' lives? Caridad Svich is the founder of NoPassport theatre alliance and press. Her play The House of the Spirits, based on the novel by Isabel Allende, premiered (in her Spanish-language version) at Repertorio Espanol in New York City and its Latin American premiere was at Teatro Mori in Santiago de Chile this summer. It receives its regional premiere (in her English-language version) at Denver Theatre Center in fall of 2010. She is currently based in New York City.  NAOMI WALLACE When I write outside of my whiteness, I am not speaking for anyone. I am instead trying to write history through characters, discovering their agency and dramatizing it on stage. What helped me in writing the black characters for Things of Dry Hours was firstly to acknowledge and examine mainstream American theater's legacy of peopling the stage with racist caricatures of Black Americans. White playwrights have too often created stereotypes of black people in order to impose a view of the world and its social relations that is as insidious as it is false. Secondly, I spent eight years, off and on, doing research for TODH. As the play came into being, inspired by Robin D. G. Kelley's brilliant book, Hammer and Hoe: Alabama Communists During the Great Depression, various artists had an important impact on its evolution. Recognizing that I was hampered (and still am) by my own blind spots (nurtured by a society that thrives on what James Baldwin calls “the lie of whiteness”) I sought out the wisdom and learning of others. Collaboration was the core that drove the project. The historians Tera Hunter and Peter Rachleff gave me critical feedback on early drafts. Kwame Kwei-Armah, who directed the play at Center Stage, urged me to rethink the ending. Director Israel Hicks highlighted the relationship between Cali and her father, Tice. Actor Karan Kendrick confronted my use of language in terms of cursing within a 1930's black family, and sent me a wonderful list of substitute swear words, my favorite being "Hot-toe-mali-no." Ruben Santiago-Hudson gave the play a multifaceted inner and outer world that I could never have imagined at its New York premiere at New York Theater Workshop. I have also written works for the stage that include Middle Easterners, Latinos, and Vietnamese. I don't know if I have the “authority” to create these characters. What I do know is that I am drawn to the still smoldering fires of resistance in American history, lit and stoked by many different people, working across lines of race and difference. In my journey as a playwright, I have been fortunate to have contact with the works of enormously intelligent minds. Alongside the writers and thinkers I have mentioned above, there is also Beth Cleary, David Roediger, Howard Zinn, Paula Giddings, W. E. B. Du Bois, bell hooks, Anne Braden and many others. Their words and texts are still my teachers. Whether I have been a worthy student I leave for others to judge. Naomi Wallace's work has been produced in the United Kingdom, Europe, the Middle East, and the United States. She was born in Prospect, Kentucky, and presently lives in North Yorkshire, England.  ALLISON WARDEN I believe that playwrights have the authority to write outside the bounds of their own ethnicity. I have encouraged a playwright friend of mine, a non-Native woman, to write a Native play, with complex Native characters. She's an amazing playwright and I would like to see more plays that focus on issues that our Native communities face and also more roles for Native actors. Ground rules that would work for playwrights would be for the playwright to write as honestly as she/he can, to trust their perspective and voice, and to also befriend a person of that ethnicity, a friend who can read the play during the process for technical authenticity. To ensure that the cultural aspects of the character reads as being authentic and believable. I've experienced being an actress reading a role for another Alaska Native group, a play written about Athabaskan people by a non-Native woman. It was an interesting experience, mostly negative. I felt that she had aspects of the play that didn't accurately portray the culture well, and it seemed at times to be a surreal mockery of the strength of the culture. I felt that her intentions were not entirely clear, and that she didn't take the time to talk to and listen to people of the culture to make sure that it wasn't outright offensive. I haven't written outside my own ethnicity, not yet. I would love to write characters outside my own ethnicity, specifically white, and also characters who are Alaskan Native, yet not Inupiaq. I would write these characters with complete conviction, pure intention and I would wait to consult with someone of the ethnicities until I have a solid draft that I could defend. I would talk to a person of that ethnicity, whom I trust, and ask questions – to make sure that I got the cultural components of the character right. At the end, I would trust my own voice and vision as a playwright and defend my authority to include these characters into my work. Allison Warden is an Inupiat performance artist and playwright who tends to focus on issues facing her communities of the Arctic. Recently her Time Immemorial, co-written with Yup'ik playwright Jack Dalton, was performed in June by Los Angeles' Native Voices at the Autry. She lives in Anchorage, Alaska.  RHIANA YAZZIE You absolutely can write outside of your ethnicity if you have a strong and detailed understanding about who it is you're writing about. You need to be sure you're not retelling old narratives that weren't created by the ethnic group you're writing about and instead were created by the dominant society's imagination. I don't think it's ok to bring in token characters to make the main characters politically correct. Also avoid blanket statements that seem to “give you permission” to write about another ethnic group instead of the detail and time needed to truly bring your character to life. I come from thinking about this subject in terms of the way Native Americans are often handled in non-Native people's plays. Sometimes there is a Native character (who by the way won't ever use contractions) who is used to make the non-Native characters and situations seem more ironic or juxtaposed, or is used symbolically. That is not writing with authority, that's writing with an agenda. Often it seems when non-Native people write about Native Americans, they are somehow trying to work out in their minds that national code of genocide – and rationalizing their own historical relationship to it, good or bad, guilty or absolved. It's a complicated story to tell when 99% of all the images about Native people we see in the theatre were created by non-Native minds (beginning with The Tempest and ongoing with this year's hit Bloody Bloody Andrew Jackson) and most of those writers have never met Native people, nor spent time in Native communities, nor read work by Native authors. With all the information out there, there's no excuse to be misinformed. If you're writing about a group you don't know, talk to them first, and if you don't get answers you like from 9 out of 10, don't listen to the 1; listen to the 9. I consider writing about other tribes that are not my own writing outside of my ethnicity. So I take a lot of time to try and get things right and talk to real people rather than relying on books or the internet. Because as a Native person I see my story being told by other people so often, I try very hard not to do that myself when I am writing. And when people tell me I got something wrong I listen. I am probably my biggest critic when it comes to writing outside my own ethnicity. Rhiana Yazzie, a Navajo playwright based in the Twin Cities, is a 2010-2011 Playwrights Center Jerome Fellow. Her play Ady was produced by Minneapolis’ Pangea World Theater in July 2010. And there you have it! Such a wide range of brilliant responses from a dynamic group of talented playwrights. It's been such a pleasure getting to read this deeply moving and insightful article. Much appreciation goes to Kia Corthron, the Dramatist Guild of America, Inc., The Dramatist magazine and these extraordinary playwrights for allowing us to read their great thoughts.